Frank

K. Ward, born in 21 March 1909,

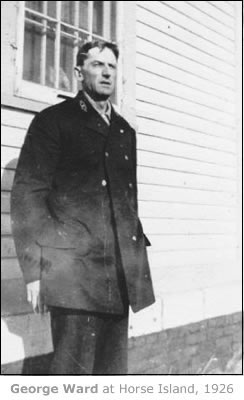

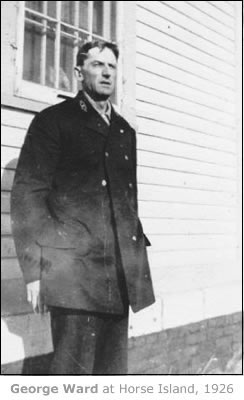

was a son of George

Ward who was a career lighthouse keeper. George's

father, James

Ward was a keeper also, as was George's father-in-law

Horace Holloway.

George served as keeper at Detroit River Light, Crossover Light, Horse

Island Light and Keeper at Oswego Harbor Light. Besides Frank were

his two brothers, Edwin

and Oswald

who also became keepers. Edwin was a career lighthouse keeper stationed

at Tibbits Point Light and at Sodus Point Lights, both on Lake Ontario.

Oswald served at stations at Buffalo and Rochester, NY.

Frank

K. Ward, born in 21 March 1909,

was a son of George

Ward who was a career lighthouse keeper. George's

father, James

Ward was a keeper also, as was George's father-in-law

Horace Holloway.

George served as keeper at Detroit River Light, Crossover Light, Horse

Island Light and Keeper at Oswego Harbor Light. Besides Frank were

his two brothers, Edwin

and Oswald

who also became keepers. Edwin was a career lighthouse keeper stationed

at Tibbits Point Light and at Sodus Point Lights, both on Lake Ontario.

Oswald served at stations at Buffalo and Rochester, NY.

These

men, as well as thousands of others, were dedicated to the U.S. Lighthouse

Service, which existed until 1940. U.S.L.H.S. servicemen served on

both coasts and all the navigable rivers in the country. There also

were floating light houses, called lightships, anchored on the ocean

in locations where land based lights were not effective. At least

one, in the mid 1930's, anchored off the mid-Atlantic coast, was lost

with all hands during a bad storm.

In 1939 with an act of

Congress, the U.S. Coast Guard took over the Lighthouse Service. Frank,

like all the active Keepers, was given the option to enlist in the

Coast Guard or become civilian employees of the Coast Guard. Frank

took the enlistment option in 1940.

In the spring of 1940,

just before the Coast Guard replaced the Lighthouse Service, Frank,

while keeper at Crossover Light, was appointed keeper at Rock Island

Light. Prior to Crossover, he had served at Lorain, Ohio Harbor Light

as Assistant Keeper and before that he was Assistant Keeper at Cleveland

Light—his first appointment after joining the Service in 1929.

In the spring of 1940,

just before the Coast Guard replaced the Lighthouse Service, Frank,

while keeper at Crossover Light, was appointed keeper at Rock Island

Light. Prior to Crossover, he had served at Lorain, Ohio Harbor Light

as Assistant Keeper and before that he was Assistant Keeper at Cleveland

Light—his first appointment after joining the Service in 1929.

At Rock Island Frank relieved

John

Belden who had served many there many years. It

was here Frank enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard and was given the

rating of Boatswain's Mate 2nd Class based on his experience and time

in service. Most other Keepers who joined the Coast Guard received

an enlisted rating. By enlisting, Frank became the last U.S. Lighthouse

Service Keeper at Rock Island.

Frank

and his family were stationed at Rock Island from 1940 to 1952.

As a member now of the Coast Guard, he continued his duties as Keeper

which included responsibility for maintaining all the aids to navigation

assigned to the station. Further, he performed maintenance and preventive

work on all the buildings, on the station launch and on tower, including

polishing the brass which held the Fresnel prisms which beamed a bright

light seen for miles up and down the river.

There

were floating buoys and crib lights to be kept in very reliable condition,

too. The 32-volt electric power for the Rock Island Light was supplied

by special batteries charged each morning by one of two motor generators.

The technology involved was quite advanced for the time. The floating

lighted buoys anchored with huge Concrete blocks called "sinkers"

were fueled by two large on-board cylinders filled with a compressed

flammable gas. The Cutter Maple was responsible for placing

the buoys in the spring and pulling them out, usually in mid-December.

They had to be pulled as the ice breakup could move them off station

and possibly cause them to sink. Some were wintered on the large buoy

dock at Rock Island and some at the depot at Cape Vincent. Maintaining

the Station launch took considerable time including laying it up for

the winter and putting it in operation in each April. Every evening

Frank made sure each light was operating. Fortunately all could be

observed with his keen eyes from Rock Island.

Frank's

eldest son David

Ward has fond memories of life at Rock Island: "Dad

was a conscientious man, always making sure the station was in good

shape and functional. He was a loving Dad, full of fun and was well

liked by our Fishers Landing neighbors. I was very close to him and

spent about all of my free time with him. It was especially great

to accompany him as he performed the lighthouse work on the island

and attending to the aids to navigation located from upriver from

Clayton to Wellesley Island light downriver from the TI Bridge. I

arose to accompany him those times he got a telephone call in the

middle of the night from District HQ in Cleveland advising that a

steamer had reported a light out. One time it was a floating lighted

buoy; too dangerous to tie up to, I nosed the launch up to the buoy

and Dad jumped onto it. I circled the boat around him until he motioned

for me to pick him up. We enjoyed fishing and hunting, and attending

the Fishers Landing community activities held during the winters.

Dad was a "jack of all trades." He was a good carpenter

and very skilled with his hands. He could repair just about anything.

It was fun being with him as repairs were made to the launch and around

everything on the station."

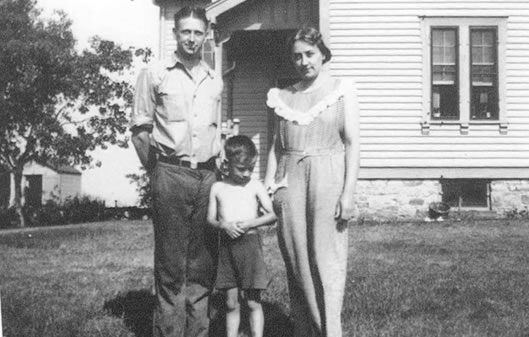

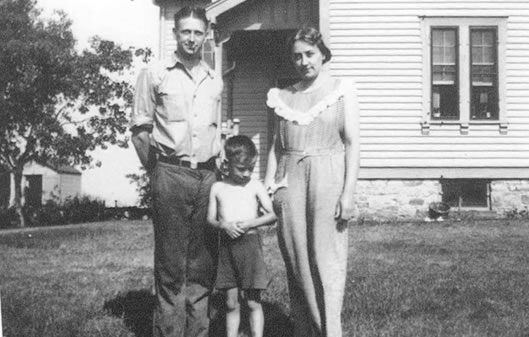

Frank

Ward with wife Sally and son David at Crossover Island

Frank

Ward with wife Sally and son David at Crossover Island |

| |

Frank

and David at Rock Island tower |

Herbert

Ward and "Jeff" on Rock Island

Herbert

Ward and "Jeff" on Rock Island |

| |

David,

Herb, Frank, and Sally Ward at Fisher's Landing in 1943 |

Frank's wife, Sara

"Sally"

(Robbins) Ward, of Clayton, once recounted an incident

which occurred during their tenure at Rock Island Light:

"A

frantic woman once came to the door wanting him to locate her husband,

a local fisherman who had failed to return home after a day on the

river. Mr. Ward was able to find him, stranded on an island

after his boat had been swept away by the wake of a large ship passing

by."

Frank

Ward is probably most remembered in Thousand Islands lore for the

events of April 15, 1951, on which he played a heroic role in a tragic

boating accident. His son David, who assisted him that day, gives

this account:

"This

is what happened that windy April day on the St. Lawrence River

off Fishers Landing, NY:

Mr. Virgil Barton, next door neighbor

and owner of several cottages and a half dozen Dundee 14 foot boats

and a couple of other makes came over to our house concerned that

he saw one of his Dundees coming toward the Landing in rough water.

There were three men who had rented the

boat and outboard motor coming in from Grennel Island which is located

about three miles south west of the Landing. The water temperature

was probably in the mid to upper 30 degrees as the ice had recently

cleared out. Dad, Virgil and I stood at the river bank in front

of our house watching them making their way in. It was a chilly

day with the wind up to at least 15 knots from the WSW. As they

came across the head of the Isle of Pines they entered the roughest

part of the river. The wind pushed the water against the head of

the island causing waves to proceed from the island against the

waves coming in from the Southwest which made for very choppy water.

As we watched, our concern for the men

was realized. A wave pushed the stern of the boat around about ninety

degrees. It quickly swamped and rolled over. The men were dressed

in heavy clothing and they had further loaded the boat down with

cottage gear. Clearly, the small boat was overloaded. One man was

large and heavy, another of medium build and the third appeared

lighter and was drowned.

Dad always put Coast Guard launch 25705

(the first two digits on CG boats and cutters always indicate the

vessel's length) in the water as soon as ice left the boathouse

slip. Sometimes he had to saw the ice and push it out of the slip

in order to be able to launch the boat as early as possible each

spring. It was good that she was in and operational that day as

no other boats of size at Fishers Landing were in the water.

So the three of us jumped in our car

and rushed to the boathouse, blowing the horn all the way to alert

neighbors of the emergency. We quickly got away from the boathouse

and headed toward the accident scene. I was running the boat and

as we came on the accident scene, Dad hurried to the forward deck

and prepared to take hold of the nearest man. Two of the men were

hanging on to the capsized Dundee. The third man had just let go

and was drifting face down past us about six feet under water, a

sight I shall never forget.

Dad, lying on the deck, four feet above

the water with the bow actively rising and falling with the waves,

managed to reach over and grab a man, who turned out to be the heaviest,

with one hand. With the other he unlashed the Danford anchor beside

him. The wind and current caused us to rapidly drift down river

until the anchor took hold. We stopped about 200 hundred feet up

river from a shoal that has a blinker light on it to warn small

craft. Virgil and I had gotten hold of the other man. We stood near

the transom on the starboard side with Virgil holding one of the

man's arms and I the other. Unfortunately, the two protruding rub

rails running parallel along the side of boat prevented us from

lifting him into the boat.

So, cold and soaked the men were totally

helpless....

Dad had the worst case, hanging onto

the man now with both his (Dad's) hands. He would have had to have

a hoist lift this poor fellow up onto the deck. Imagine the strain

he experienced as the launch worked with the seas. Dad's chest lay

painfully across the oak trim mounted on the gunnel. Dad later told

me his fellow kept saying "don't let go." It's estimated

we were in this situation about an hour waiting for help to come.

Harry Chalk of Chalk and Son's boat livery

own a forty foot enclosed boat used to ferry folks to and from their

island cottages. Mom called Harry and told him of our situation.

His boat was named "That's Her." She was still laid up

on timbers in Harry's boathouse. As he hurried to prepare its engine

and launch the boat, men from around Fishers Landing were arriving

to assist. They made good time getting the boat in the water and

the engine running. Several men jumped aboard. Shortly, they were

along side our launch. Two rushed forward to relieve Dad and managed

to move his man aft past the cabin, and with the help of more men

lifted him into the launch. Others lifted our man into the boat.

It was George W. Swallow that drowned.

Fred Jurrier (Dad's man) unfortunately died of hypothermia either

on the launch or shortly after being removed from the launch. I

watched as he was hauled aboard and appeared to be alive. He was

placed on the engine box for some warmth. Harry Hollensteiner was

hauled aboard alive and survived. I do not believe there was time

or know-how to perform artificial respiration. The anchor was lifted

and we headed for shore.

Dad came into the launch's cabin and

sat on a side thwart and lit a cigarette. He was tired but seemed

to be OK. He asked if I was all right.

We reached shore shortly where many onlookers

were as well as the Clayton, NY fire department firemen who began

working on Mr.Jurrier.

The CG District Office sent a young seaman

to temporarily relieve Dad. He and I, using the station skiff, dragged

for Mr. Swallow's body, but we didn't find it.

Dad's ribs and associated cartilage were

badly injured. Word quickly spread that Dad had suffered a heart

attack which fortunately was not true. He was terribly sore and

had bed rest for about two months at home. We got hold of a hospital

bed and placed it in our living room. He maintained a good attitude,

but was sad about the loss of life. He had just turned forty-two

years of age.

There were various articles written about

the accident over the years and included statements that his health

was "never" the same again. It did take some time for

the soreness to clear up, of course. He resumed his duties by July

1951 and spent his free time studying for the Chief Petty Officer

exam, a two day affair taken on the Cutter Maple with the captain

as proctor. Dad passed the rigorous exam and was promoted to Chief

Boatswain Mate a month or so later."

Ward's

letter of commendation for his heroic actions on 15 April 1951.

Frank

Ward's career with the Coast Guard soon took him away from the shores

of the Thousand Islands, as son David recalls:

"By

early 1952 we learned that Rock Island Light Station did not rate

a CPO. In June of 1952 Dad got orders to report to the Coast Guard

Base in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. It was decided that Mom and us boys

would come home to the Landing after dropping Dad off at the CG

Station in Milwaukee—the folks didn't want to cause us to

change schools, among other considerations.

Before we left, Mr. John

Van Ingen was appointed keeper of Rock Island Light

Station to relieve Dad."

Frank

Ward (second row, at left) with the Milwaukee crew, in formation.

In late 1952 while

on duty at the Milwaukee Coast Guard Station, Frank was afflicted

by a condition that took him to the veterans hospital there. It was

serious enough that he was eventually placed on temporary retirement

and returned home to Fishers Landing. He applied for and was granted

regular retirement in 1957. As David continues:

"He

adjusted well and got a job as foreman of the carpenter shop at

what is now Fort Drum, near Watertown, NY.

Dad enjoyed many productive years at

Fishers Landing. I was impressed that, among other projects, he

built a substantial boat dock attached to his property and later

purchased two lots across from the house. He built a cobblestone

cottage on one lot and he and Mom rented it during summers—it

is now the Fishers Landing post office.

Unfortunately, he was afflicted with

what was years later determined to be Crohn's Disease. He died from

this terrible disease at age seventy-nine."

Frank

died Monday, 2 May 1988, in Edward John Noble Hospital's Skilled

Care Unit, Alexandria Bay. The funeral was held at 11 a.m. Wednesday

at the Foster-Hax Funeral Home, Pulaski, with Rev. Dale E. Austin,

pastor of the Clayton and Depauville United Methodist churches,

officiating.

Mrs. Sara Ward

remained at Riverview Apartments after her husband's passing. On

Sunday, 22 July 1990, at age 81, she died at the House of the Good

Samaritan, Watertown. Her funeral was held at 10 a.m. Wednesday

at the Foster-Hax Funeral Home, Pulaski, with the Rev. Elizabeth

Mowry, pastor of Park United Methodist Church, Pulaski, officiating.

Both Frank and Sara

are buried in South Richland Cemetery, Fernwood, Oswego County,

New York.

Father and son, 1960.

Frank

K. Ward, born in 21 March 1909,

was a son of George

Ward who was a career lighthouse keeper. George's

father, James

Ward was a keeper also, as was George's father-in-law

Frank

K. Ward, born in 21 March 1909,

was a son of George

Ward who was a career lighthouse keeper. George's

father, James

Ward was a keeper also, as was George's father-in-law

In the spring of 1940,

just before the Coast Guard replaced the Lighthouse Service, Frank,

while keeper at Crossover Light, was appointed keeper at Rock Island

Light. Prior to Crossover, he had served at Lorain, Ohio Harbor Light

as Assistant Keeper and before that he was Assistant Keeper at Cleveland

Light—his first appointment after joining the Service in 1929.

In the spring of 1940,

just before the Coast Guard replaced the Lighthouse Service, Frank,

while keeper at Crossover Light, was appointed keeper at Rock Island

Light. Prior to Crossover, he had served at Lorain, Ohio Harbor Light

as Assistant Keeper and before that he was Assistant Keeper at Cleveland

Light—his first appointment after joining the Service in 1929.